It was clear from the outset that my crime novel would be set in the music world. I grew up with music and have been in the business for years, so I know plenty about how things in the music world work – what is conceivable and realistic. Simply put, it is easier to describe a milieu that you are very familiar with. I found it even more fun structuring the story around a dual timeline.

I thought that the ‘Messiah’ – a violin worth over 30 million euros in insurance, which is never allowed to be touched and whose authenticity is still privately doubted to this day – would be a good hook for a crime story. I wasn’t setting out to advocate for one side or another in the case of the ‘Messiah’, but rather to invent a third, completely new possibility. I came up with the idea of a twin of the ‘Messiah’, called ‘Bocciolo di Rosa’ (‘Rosebud’) – an even more beautiful violin which has been missing for centuries. While the information about the ‘Messiah’ – the most famous and most valuable violin in the world – is based on historical facts, both the ‘Rosebud’ and its path from 1716 until the present day are the product of my imagination. In the novel, this instrument is even more valuable than the Messiah because Stradivari had taken the unusual step of choosing its name himself, and inscribing it next to the hand-drawn rose on the violin plate. The setting for the novel then essentially chose itself: this would ultimately be the story of Antonio Stradivari and his two violins. For me, the story could only play out in Italy, which remains beyond question the most distinguished home of violin makers to this day. A family drama like the one in ‘Tödliche Sonate’ could of course happen anywhere in the world.

As a concert violinist I often have old – sometimes very old – instruments in my hands. It makes me wonder where these antique violins were, and whose hands they were in, before they ended up in mine. Where were these instruments a hundred, two hundred or three hundred years ago – who was playing them then? I love imagining the lives of violin makers, their work and the times they lived in. What would it have been like, for example, to meet Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume and watch over his shoulder as he worked – or to be allowed to look around Antonio Stradivarius’s mystical workshop? Or to exchange a few words with Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù while he made the finishing touches to his legendary violin “Il Cannone”?

One day I decided to bring some of these extraordinary characters to life in a novel. It was exciting, but not easy, to operate in a time period that one only knows from books or stories. Mixing facts and fantasy was, ultimately, a great adventure. All the characters from the past – both the ones the reader encounters directly in the novel, such as Antonio, Francesco, Omobono, Paolo and Cesare Stradivari, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, Camillo Sivori and Francesco Sfilio –as well as those who are only mentioned – like Count Cozio di Salabue and Luigi Tarisio – lived at that specific time. The only change I made was in the last scene with Francesco Sfilio, whose career I extended by a few years with the ‘Messiah’s’ twin in mind (in reality this outstanding violinist had already lost his eyesight and given up his concert career by 1910). The other characters in the novel are made up, although some of them are inspired by real people; Commissario di Bernardo is very similar to my south Italian adoptive father, for example, who is also a fan of ties and good food. The story needed a violinist, and I must confess that I identify somewhat with Arabella Giordano myself. The concert agent Cornelia Giordano does have some realistic traits, but is for the most part a product of my imagination.

The narrative perspective is dominated by Commissario Di Bernado’s point of view, but I decided to include short sequences throughout from the murderer’s perspective as well, describing his brutal thoughts and actions. And, of course, I tell the story of the ‘Rosebud’ from one further perspective, on a second timeline.

My writing was also inspired by my own beloved violin: a lovely J.B. Vuillaume from 1870, a precise copy of the ‘Messiah’, which is part of my and my partner Manrico Padovani’s private collection. It was a brilliant feeling to immerse myself and my violin in these musical characters – both the contemporary ones and those from the eighteenth century – particularly in the parts where I am describing concerts or daydreaming with a violin.

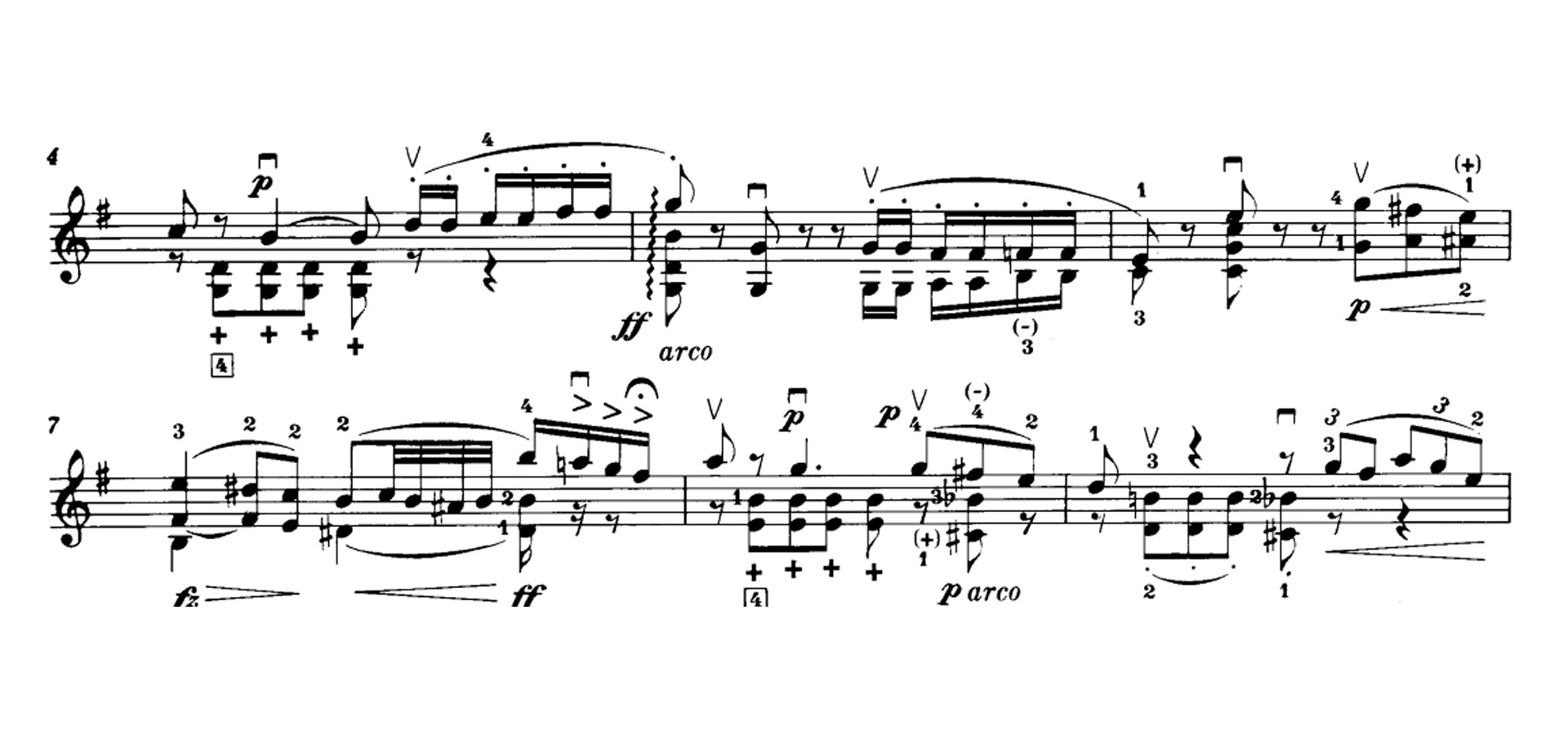

Several wonderful pieces are played in ‘Tödliche Sonate’, all of which – with the exception of the Beethoven Piano Sonata – are also part of my concert repertoire. The virtuoso piece ‘Die letzte Rose des Sommers’ (The Last Rose of Summer) by H.W. Ernst, which the composer dedicated to A. Bazzani, is particularly fitting for the story of the ‘Rosebud’.

Arvo Pärt: „Tabula Rasa“ for 2 violins, string orchestra and prepared piano

César Franck: Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano

George Gershwin – Jascha Heifetz: „Summertime“ from the Opera „Porgy and Bess“

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violinromanze Nr. 2 in F (Op.50)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Klaviersonate Nr. 8, Op. 13, „Pathétique” (Adagio cantabile)

Niccolò Paganini: „I Palpiti“

Johann Sebastian Bach: Giga aus der Partita Nr. 3 für Violine solo

Johann Sebastian Bach: Chaconne aus der Partita Nr. 2 für Violine solo

Johann Sebastian Bach: Sarabande aus der Partita Nr. 2 D-Moll für Violine solo, BWV 1004

Camillo Sivori: Fantasie über „Il Trovatore“ (Giuseppe Verdi)

Arcangelo Corelli: La Follia

Eugene Ysaye: L’Aurore aus der Sonate für Violine solo G-Dur Op. 27 Nr. 5

Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst: Die letzte Rose des Sommers